Share this.

By Nancy Finlay

Political boundaries can be arbitrary things, accidents of history that might have turned out differently if a certain sequence of historical events had a different outcome. Even today, in some parts of the world, boundaries between nations remain hotly contested matters. In contrast, the boundaries of the New England states seem to be immutable and the existence of separate places called Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island seems to have been inevitable. But what if history had taken a different turn back in the 17th century? It is possible that there might have been a state of New Haven stretching from the Connecticut River to the Delaware River and including all of Long Island and New York City.

The beginnings of the New Haven Colony were very similar to the beginnings of the Connecticut Colony. Like Thomas Hooker, John Davenport was a popular Puritan minister who fled to Holland to escape persecution by the established Church of England. Like Hooker, Davenport decided to immigrate to America in search of religious freedom, and like Hooker, a substantial portion of his congregation accompanied him. Both groups of Puritans wound up in Boston in the early 1630s and both became dissatisfied with what they found there. Hooker struck out overland to establish Hartford in 1636. Davenport’s party sailed into New Haven harbor to establish a new colony in 1638.

Davenport Limner, Reverend John Davenport, 1670, oil on canvas – Yale University Art Gallery

Although there were many basic similarities between the settlers of Hartford and New Haven, there were also differences. Hooker’s congregation was from the small inland town of Chelmsford. Davenport’s parishioners were, in part, rich London merchants. In addition, there were religious differences between the two sets of Puritans. Though both groups sought to “purify” the Anglican church, stripping it of ritual and returning it to the simplicity described in the Bible, Davenport and his followers proved much more extreme, limiting church membership and participation in the government of the new colony to a greater degree.

The location of the New Haven Colony on Long Island Sound afforded many more options for trade and expansion than the site of Hartford, located inland on the Connecticut River. Exploring parties from New Haven probed both sides of the sound and ventured as far south as Cape May and Cape Henlopen in present-day New Jersey and Delaware. By 1640, New Haven had acquired the eastern end of Long Island, including the towns of Southold and Southhampton, as well as additional lands to the west towards New Netherland. In 1641 and 1642, they purchased lands on the Eastern Shore and along the Delaware River from the Native Americans, despite conflicting claims from New Netherlands and a Swedish settlement at Fort Christina. In 1643, the New Haven Colony absorbed the previously independent plantations of Guilford, Milford, and Stamford, consolidating its position on the mainland.

In spite of ongoing disputes with the Dutch over the settlements on the Delaware, trade with New Amsterdam was brisk and relations were generally good. New Amsterdam relied on New Haven for provisions, including beef, pork, livestock, dairy products, peas, and flour, which it exchanged for furs and skins, wines and liquors, and ships. New Haven also enjoyed a close relationship with the neighboring Connecticut Colony, with which it had many interests in common. In addition to the coastal trade, New Haven’s fine harbor easily accommodated ocean-going vessels, and shipbuilding began there at an early date. In 1646, Thomas Hooker entrusted the manuscript of his Survey of the Summe of Church-Discipline to a New Haven vessel, which unfortunately sank in the North Atlantic on its way to England.

New Haven colonists welcomed news of the outbreak of the English Civil War, the deposition and execution of King Charles I, and the establishment of a Puritan government in England under Oliver Cromwell, as did other Puritan colonies. Many New England Puritans returned to England to take part in the fighting or to serve in Cromwell’s government, or simply to take advantage of the fact that their party was now in power and they no longer faced persecution. Davenport himself seriously considered returning to England, but in the end decided to remain in the colony he helped to found. The Puritan government in England looked favorably upon the Puritans in New England, and the future of the New Haven Colony seemed secure.

In the spring of 1660, when rumors began to reach New Haven that Charles II had been restored to the English throne, Davenport at first refused to believe it, convinced that the triumph of the Puritan cause was God’s will. By the end of July, however, Edward Whalley and William Goffe had arrived in Boston, fleeing a death sentence. The two men had voted for the execution of Charles I and were now condemned as regicides. As soon as Davenport heard of their arrival, he invited them to New Haven. They stayed with him for eight weeks, then were moved from place to place throughout the colony, from one safe house to another, while royal agents sought them in vain. English authorities never apprehended them.

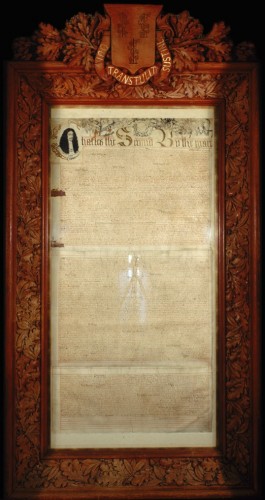

Charter of the Colony of Connecticut, 1662 – Connecticut State Library

Unlike the Massachusetts Bay Colony, neither the New Haven Colony nor the Connecticut Colony had a royal charter, so with the restoration of the monarchy, their existence was in question. In 1661, John Winthrop Jr, governor of the Connecticut Colony, was chosen to represent both Connecticut and New Haven, and to petition Charles II for a charter authorizing the two separate colonial governments. From the Connecticut point of view, Winthrop’s mission was an overwhelming success. The charter he obtained in 1662 essentially confirmed Connecticut’s Fundamental Orders and established very broad territorial boundaries for the colony. From the New Haven point of view, the Charter of 1662 was a disaster: by its provisions, the New Haven Colony ceased to exist, and instead found itself absorbed by the colony of Connecticut.

The news devastated the founders of the New Haven Colony, but many of the outlying towns that chafed under New Haven’s strict rule and limited franchise were glad to become part of Connecticut. Some New Haven citizens considered immigrating to New Netherland, where the Dutch Governor, Peter Stuyvesant, welcomed them, but in August 1664, an English fleet forced the surrender of New Amsterdam, and New Netherland became a part of the surrendered territory eventually known as New York. Forced to choose between Anglican New York and Puritan Connecticut, the last holdouts in New Haven finally agreed to union with Connecticut in January 1665. John Davenport remained in New Haven until 1668, when he returned to Boston. He died in Boston in 1670, embittered and surrounded by controversy.

The rivalry between New Haven and Hartford lasted for centuries. For many years, Connecticut had two state capitals, one in each city, and the legislature moved back and forth between the two. This unusual and unwieldy situation lasted until 1875. Richard Upjohn completed his monumental new state capitol building in Hartford three years later. Today few people remember but that for a turn in fortunes, Connecticut might have been two states instead of one.

Nancy Finlay grew up in Manchester, Connecticut. She has a BA from Smith College and an MFA and PhD from Princeton University. From 1998 to 2015, she was Curator of Graphics at the Connecticut Historical Society.